January 21, 2026

AddressSanitizer (ASan): Your Safety Net for C Memory Bugs

Why C Programming Needs a “Sanitizer”

C is a powerful low-level programming language, but it does not automatically protect you from common memory mistakes. For example, in languages like Java or Python, accessing an array out of bounds will immediately throw an error or exception. In C, the program will not stop you – it will attempt the invalid memory access with unpredictable results[1]. The C standard calls such situations undefined behavior, meaning anything can happen: you might read garbage data, corrupt other variables, or crash the program. This lack of built-in safety is by design – C was created for efficiency and gives the programmer full control (and responsibility) over memory.

For beginners who have just learned about pointers and arrays, this means it’s very easy to accidentally write past the end of an array or use a pointer incorrectly. These mistakes are normal and expected when learning C, but they can lead to tricky bugs. Memory errors like buffer overflows (going past an array’s boundaries), use-after-free (using memory after giving it back to the system), or memory leaks (forgetting to free memory) might not cause an immediate obvious crash. Instead, they can silently corrupt data or cause random crashes later, making them hard to debug. In fact, some of the worst software vulnerabilities in real life (like security exploits) have been due to memory corruption bugs[2]. Clearly, we need a way to catch these issues early, especially when you’re just starting out.

What Is AddressSanitizer (ASan)?

AddressSanitizer (ASan) is a tool that acts like a safety net for C (and C++) programs, helping you catch memory mistakes as soon as they happen. It’s built into modern compilers (GCC and Clang), originally developed by Google[3]. You enable it when compiling your program, and it instruments your code to automatically detect a wide range of memory errors at runtime. In plain language, AddressSanitizer adds extra checks around every memory access (like reading from or writing to an array or pointer). If you make a mistake, the program will stop immediately and print a detailed error message explaining what went wrong[4][5].

What kinds of bugs can ASan catch? Quite a lot, including:

- Buffer overflows/out-of-bounds access: Going outside the bounds of an array (on the stack, heap, or global memory)[6].

- Use-after-free: Accessing heap memory after you’ve freed it (deallocated it)[7].

- Use-after-scope: Using a pointer to a local variable after the function returns (pointer to invalid stack memory)[7].

- Double free or invalid free: Freeing the same memory twice, or freeing memory that wasn’t allocated.

- Memory leaks: Memory that was allocated but never freed (AddressSanitizer’s leak checker, called LeakSanitizer, will report this)[8].

Instead of a mysterious crash or “segmentation fault,” ASan will tell you exactly what happened and where. For example, rather than just crashing, it might print an error like “heap-buffer-overflow on address 0x12345678” and even show the line of code that caused it and where that memory was allocated[9]. This kind of clear feedback is incredibly helpful. In fact, if you overflow an array, ASan will not only tell you that you went out of bounds, but also where the array was originally allocated, dramatically reducing the time to track down the bug[10]. In short, AddressSanitizer turns hard-to-find memory bugs into easy-to-understand error messages.

Why Use ASan Early in Your C Learning?

When you’re learning C, using AddressSanitizer from the start can build good habits and save you from a lot of frustration. Memory bugs in C can be unpredictable – your program might appear to work and then crash under different conditions. ASan helps by catching the bug at the moment it occurs, when you run your program, so you don’t have to guess what went wrong. This gives you immediate feedback on mistakes, which is great for learning. You’ll start to recognize common errors (like “stack-buffer-overflow” or “use-after-free”) as normal stepping stones in the learning process, not catastrophic failures. Each ASan error is like a friendly detective giving you clues to fix the code.

Moreover, using ASan encourages a debugging mindset. Instead of feeling bad about a bug or blindly trying to “patch” it, you can investigate the ASan report to understand the root cause. The tool teaches you to be curious about memory: Why did I get an out-of-bounds error? Did I miscalculate an index? By treating memory bugs as puzzles to solve (with ASan’s hints) rather than just mistakes, you gain confidence in writing C code. Even experienced C developers use tools like ASan to catch issues – so as a beginner, you’re in good company using it. The goal is that over time you’ll internalize what causes these errors, but you’ll always have ASan as a safety net to catch the ones you miss. Essentially, AddressSanitizer is essential for learning C safely: it lets you experiment and make mistakes, then learn from those mistakes quickly, instead of spending hours hunting down weird bugs.

How to Enable AddressSanitizer in Your Programs

Using AddressSanitizer is straightforward. Since it’s built into the compiler, you just need to add a special flag when compiling your C code. Both gcc and clang support ASan. For example, if you have a program program.c, you can compile it with AddressSanitizer like this:

gcc -fsanitize=address -g -o program program.c

Let’s break down that command:

- -fsanitize=address tells the compiler to include AddressSanitizer instrumentation[11].

- -g includes debug symbols (this is optional but recommended during development). Debug symbols make ASan’s error messages more informative by including line numbers[12].

- -o program just names the output executable.

If you’re using Clang instead of GCC, the same -fsanitize=address flag works. On Windows with Visual Studio, there’s a similar option (/fsanitize=address in recent MSVC compilers)[11].

Once you compile with ASan, run your program as usual (for example, ./program). AddressSanitizer’s checks are now active. If your program has a memory bug that ASan can detect, it will print an error report to the terminal and typically abort the program after the issue is detected. If there are no memory errors, your program will run normally and you won’t see any ASan messages.

One important note: AddressSanitizer adds some performance overhead (your program will run slower and use more memory, which we’ll discuss later). This overhead is fine for testing and learning. But it means you usually won’t include ASan in the final version of a program you ship to users. For now, as a learner, you can compile all your small practice programs with -fsanitize=address by default, to catch bugs early. Next, let’s walk through some concrete examples of common memory errors, and see how ASan reports them.

Example 1: Stack Buffer Overflow (Array Out-of-Bounds)

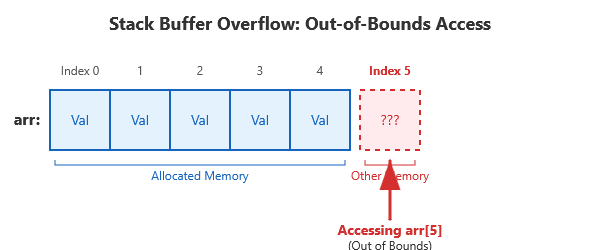

A stack buffer overflow occurs when you go past the end (or before the beginning) of an array that’s allocated on the stack (typically a local array inside a function). In simpler terms, imagine you have an array of a fixed size, but you try to access or write to an index that’s outside that range. C won’t stop you from doing this, but it’s a bug that can corrupt memory.

(Diagram: A diagram of an array with 5 slots indexed 0 through 4, and an arrow trying to access index 5 outside the array’s boundary, illustrating an out-of-bounds access.)

Let’s look at a small C program that has an array out-of-bounds error:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[3] = {1, 2, 3};

printf("Element 0 is %d\n", arr[0]);

printf("Element 3 is %d\n", arr[3]); // Bug: index 3 is out-of-bounds

return 0;

}In this code, arr is an array with 3 elements (valid indices are 0, 1, 2). The line arr[3] is a mistake – it tries to access a fourth element that doesn’t exist. Without AddressSanitizer, this program might run and print some arbitrary number for arr[3] (or it might crash) because we’re reading memory that isn’t part of the array. With ASan enabled, let’s see what happens.

Compile and run with ASan:

gcc -fsanitize=address -g out_of_bounds.c -o out_of_bounds

./out_of_bounds

Suppose we run it; AddressSanitizer should catch the error. The output from ASan will look something like this:

Element 0 is 1

=================================================================

==12345==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: stack-buffer-overflow on address 0x7ffeefbba0ac

READ of size 4 at 0x7ffeefbba0ac thread T0

#0 0x555555556789 in main /home/user/out_of_bounds.c:6

(The ASan output continues with more details, including a memory map and a summary line.)

Breaking this down: the program printed “Element 0 is 1” normally. Then ASan detected a problem and printed an error. The message “stack-buffer-overflow on address …” tells us exactly what the issue is: we accessed a stack array out of its bounds. It even specifies that it was a READ of size 4 at that address (in this case, reading an int which is 4 bytes) and shows that it happened in main at our source line 6[13]. The #0 … in main /…/out_of_bounds.c:6 is part of the stack trace – it’s telling us the exact line of code where the invalid access occurred (line 6 in our code). This is extremely helpful: we know we did something wrong at arr[3], and indeed line 6 is the printf with arr[3].

If we scroll further in the ASan output (not all of it is shown above), it would also show a SUMMARY line indicating the type of error (stack-buffer-overflow) and possibly more context. ASan might also print a bit about the memory region around that address. For example, it often shows a “shadow bytes” section with a legend, which is internal debugging info (red zones, etc.). As a beginner, you don’t need to worry about the shadow byte legend or the hex dump that ASan prints. The key parts are the error description and the stack trace. In this case, ASan basically pointed out: “Hey, you tried to read 4 bytes past the end of a stack array, at this line in your code.” That’s enough information to realize we should fix the code (likely by using arr[2] or correcting a loop boundary).

AddressSanitizer turned what would have been an invisible bug (or a confusing wrong value) into a clear error message. We can now confidently fix the out-of-bounds access. The takeaway: if you ever see “stack-buffer-overflow” from ASan, it means you accessed a local array outside its valid range. The fix is usually to correct the index or allocate a bigger array if needed.

Example 2: Heap Use-After-Free

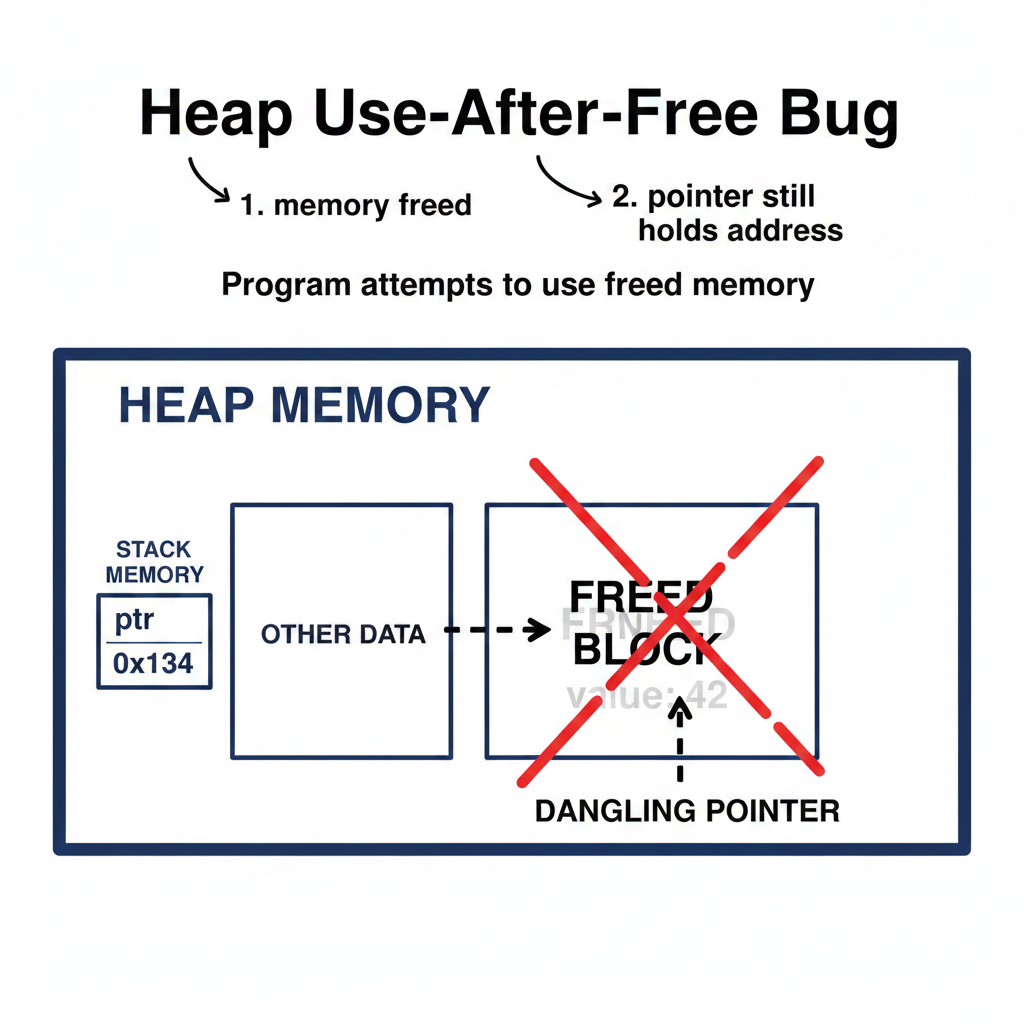

A use-after-free bug happens when you free a block of memory on the heap, but then later your program still uses that memory (either reading from it or writing to it). After freeing, that memory is no longer yours – using it is like reading a book after you’ve returned it to the library. The data might still look intact for a while, but the memory could be given to another part of the program, leading to corruption. C does not automatically zero out or invalidate your pointer when you free memory, so it’s easy to accidentally use a “dangling pointer” (a pointer that refers to freed memory)[14].

(Diagram: A illustration of a heap memory block being freed. Imagine a box labeled “memory” that has been freed (maybe marked with an X), while a pointer variable still points to that box. This represents a dangling pointer after free.)

Consider this simple program with a use-after-free bug:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int *ptr = malloc(sizeof(int));

*ptr = 42;

free(ptr);

printf("Value: %d\n", *ptr); // Bug: using memory after free

return 0;

}Here we allocate an integer on the heap with malloc, store the value 42 in it, and then free that memory. The last line tries to printf the value via *ptr after it’s been freed – this is a use-after-free. Without ASan, this might actually print “42” as if nothing is wrong (because that memory hasn’t been reused yet, in this small program). Or it could print garbage, or crash – it’s undefined. Let’s see what AddressSanitizer says.

Compile and run with ASan:

gcc -fsanitize=address -g use_after_free.c -o use_after_free

./use_after_free

ASan will catch the invalid memory access. The error output will be along these lines:

=================================================================

==98765==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: heap-use-after-free on address 0x602000000010

READ of size 4 at 0x602000000010 thread T0

#0 0x555555556abc in main /home/user/use_after_free.c:7

#1 0x7f8abcd12345 in __libc_start_main (libc.so.6+0x…)

// … additional ASan info …

Let’s interpret this. The message “heap-use-after-free” tells us the type of error: we used heap memory after freeing it. It pinpoints the memory address and the fact that we performed a READ of size 4 at that address. (In our code, *ptr in the printf is reading 4 bytes, an int.) The stack trace shows that this happened in main at line 7 of our source (which is the printf(“Value: %d”, *ptr) line)[13]. So we immediately know: line 7 tried to access memory that was freed.

ASan’s report for use-after-free is very informative. After the initial lines, it will also tell you where the memory was freed and where it was originally allocated. In our example output, you would see something like:

… 0x602000000010 is located 0 bytes inside of 4-byte region [0x602000000010,0x602000000014)

freed by thread T0 here:

#0 0x555555558888 in free (somewhere in ASan internals)

#1 0x555555556aa0 in main /home/user/use_after_free.c:6

previously allocated by thread T0 here:

#0 0x555555558AAA in malloc (asan_malloc in ASan internals)

#1 0x555555556980 in main /home/user/use_after_free.c:5

The above (simplified for clarity) tells us: the memory in question was freed at line 6 in our code (that’s the free(ptr) call) and it was allocated at line 5 (ptr = malloc(…)). ASan is essentially giving us a history of that memory[15]. This is extremely useful for debugging – it’s saying “you freed this memory here, but then you tried to use it later (at this other place)”. With this information, you can quickly realize the mistake: the printf should not be using ptr after free. The fix could be to move the free(ptr) to after you’re done using the memory, or simply remove that printf (or set ptr to point to valid memory before using it).

The ASan output for a use-after-free is a bit longer than for a simple buffer overflow, and it can look intimidating at first (there’s even a “shadow byte legend” like fd meaning freed memory, etc.). But as the report itself says: it’s not as bad as it looks[16]. The key sections to pay attention to are:

- The top part telling you the type of error (heap-use-after-free) and where it happened in your code (line number).

- The section “freed by here” with a stack trace, giving the location of the free call.

- The section “previously allocated by here”, giving the location of the malloc (or allocation).

This is usually enough information to debug the issue[17]. In our case: memory allocated at line 5, freed at line 6, then used at line 7 – clearly an error in logic. We can fix our program by not using ptr after freeing it (for example, we could free after printing, or not free at that point if we still need the data).

By catching use-after-free, AddressSanitizer helps you avoid a class of bugs that can be very hard to diagnose otherwise. Often, a program with a use-after-free might crash much later or corrupt data elsewhere. ASan stops it at the point of misuse and shouts out the problem, turning a possible random crash into a clear actionable error message. Remember, a heap-use-after-free in ASan’s output means “you are touching heap memory that was already freed” – check where you called free and make sure you didn’t continue to use that pointer.

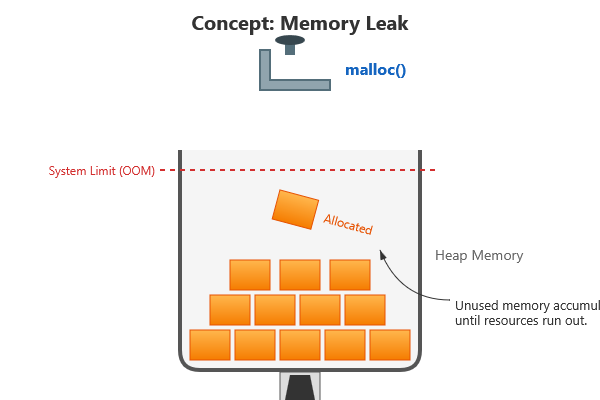

Example 3: Memory Leak

A memory leak occurs when a program allocates memory (for example with malloc) but never frees it, even though it’s no longer needed. If a program with leaks runs for a long time or allocates a lot in a loop, it can end up using more and more memory, eventually exhausting the system’s memory. In short-lived programs a small leak isn’t usually catastrophic, but it’s still a bug and a bad habit. As you learn C, you should practice freeing what you allocate. AddressSanitizer can help by detecting leaks – it will report any allocated heap memory that wasn’t freed by the time the program exits[18].

Here’s a simple program with a memory leak:

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int *data = malloc(100 * sizeof(int));

data[0] = 123; // use the allocated memory (optional)

// Oops, we forgot to free 'data'

return 0;

}This program allocates space for 100 integers, uses it (storing 123 in the first element), and then exits without freeing the memory. That’s a leak of whatever size we allocated (400 bytes in this case, since 100 ints × 4 bytes each = 400 bytes). Let’s see how ASan reports this.

Compile and run with ASan:

gcc -fsanitize=address -g leak.c -o leak

./leak

The program’s functionality is trivial and produces no output itself, but AddressSanitizer will detect the memory leak when the program ends. The ASan output will include a section from the LeakSanitizer (which is integrated with ASan on most systems). It will look like this:

=================================================================

==54321==ERROR: LeakSanitizer: detected memory leaks

Direct leak of 400 byte(s) in 1 object(s) allocated from:

#0 0x555555558AAA in malloc …

#1 0x555555556cde in main /home/user/leak.c:4

SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: 400 byte(s) leaked in 1 allocation(s).

The important parts of this report: “detected memory leaks” and specifically a direct leak of 400 bytes in 1 object. It even shows that the allocation happened in main at line 4 of leak.c[19]. That’s our malloc call. There’s no mention of a free in the stack trace because we never called free – that’s exactly the problem. The summary says 400 bytes were leaked in 1 allocation.

In this way, ASan (with LeakSanitizer) tells us that we forgot to free something. With the line number given, it’s easy to locate the allocation in the code and ensure we add a corresponding free when the memory is no longer needed. For our tiny example, we would just add free(data); before return 0; in main. If you fix the leak and run again, ASan will stay silent (no news is good news).

Memory leaks might not crash your program, but they do increase memory usage. Over time or in memory-limited environments, leaks can cause your program to run out of memory. That’s why it’s important to catch them. AddressSanitizer’s leak detection is very handy for verifying that your program cleaned up all the memory it allocated. As a beginner, it’s a great practice to run your code with ASan and ensure you get the “All heap blocks were freed — no leaks are possible” message (or simply no leak reports) at program exit. This helps you develop the discipline of pairing each malloc with a free.

When (and When Not) to Use AddressSanitizer

By now, you can see that AddressSanitizer is a powerful tool for catching memory errors. So when should you use it? For learning and development, almost always! Here are some guidelines:

- Use ASan during development, testing, and learning: Whenever you write C code (especially if you’re new to pointers and manual memory management), compile it with -fsanitize=address for debugging runs. It will catch many mistakes immediately and provide helpful feedback[10]. This saves you from spending hours tracing a weird bug. Even for experienced developers, running test suites or debug builds with ASan is a common practice to find hidden bugs.

- Use ASan for programs of any size during testing: Whether it’s a small homework assignment or a larger project, ASan can be enabled to ensure memory safety. It’s better to catch a bug in your tests than have it slip into a final product.

However, AddressSanitizer is not intended for every situation:

- Do not use ASan in production releases: An ASan-instrumented program is slower and uses more memory than a normal program. In practice, AddressSanitizer can make a program use about 2x more memory and run 1.5–2x slower due to the added checks[20]. This overhead is totally acceptable for testing, but for a production (user-facing) build, it’s too much. You wouldn’t want the version of your program that you ship to customers to suddenly run at half speed and use twice the RAM. Therefore, you should disable ASan for the final build of your program that you deploy or release[21]. (In fact, ASan will also print a lot of internal diagnostics which you wouldn’t want leaking into user logs.)

- Avoid ASan on resource-constrained systems: If you’re working on an embedded device or an environment with very limited memory, you might not be able to afford the overhead of ASan even during debugging[22]. In such cases, you may rely on other techniques or specialized tools for those platforms.

- ASan isn’t a substitute for logic testing: AddressSanitizer is specifically for memory errors. It won’t catch other kinds of bugs (like incorrect algorithms or logic errors). So while it’s great at what it does, you still need to test your program’s functionality. Use ASan alongside other testing and debugging methods – it’s one piece of the toolbox.

In summary, enable ASan when debugging and testing your C programs, but disable it for the production build or performance-critical runs. Typically, developers have it on in “debug mode” and off in “release mode.”

Embracing a Debugging Mindset with ASan

One of the best things about using AddressSanitizer early in your C journey is that it encourages you to view bugs as learning opportunities rather than failures. When ASan flags an error, you don’t need to panic or feel discouraged. Instead, treat the error message as a clue. It’s telling you what happened and where – almost like a teacher or a puzzle hint. For example, if you see “stack-buffer-overflow”, you now know that means an array was accessed out of bounds; you can use the stack trace to find the exact line and then reason about why that index was wrong. If you see “heap-use-after-free”, you know you need to check where you freed memory and make sure you’re not using it afterward. This approach turns debugging into a logical investigation, which is a crucial skill in programming.

It’s also important to normalize the fact that memory bugs are common, especially in C. Even veteran C programmers introduce bugs; the difference is that they use tools and experience to find and fix them. By using ASan, you’re equipping yourself with a professional-grade tool from day one. Each time you catch a bug with ASan and understand it, you’re building your intuition about how C manages memory. Over time, you’ll start avoiding certain mistakes, but you’ll likely still use ASan regularly because it can catch the subtle issues that even experts miss.

Finally, celebrate the bugs you catch! It may sound odd, but when ASan prints an error, that’s a success – it means a dangerous bug didn’t slip past you. You found it, and now you can fix it proactively. This beats finding out later when it causes a crash at an inconvenient time. So, keep AddressSanitizer as your coding companion while you learn C. It will give you the confidence to play with pointers and memory, knowing that if you step out of bounds, ASan will be there to point it out. By incorporating ASan into your early development workflow, you’re developing strong debugging habits and a deeper understanding of how your C programs use memory. Happy coding, and may your memory bugs be caught early and often!

Sources: AddressSanitizer official documentation and tutorials[23][24][25]; Ohio Supercomputer Center ASan guide for examples[26][27]; Can Özkan’s Medium article for ASan usage and tips[6][20].

[1] Accessing array out of bounds in C/C++ – GeeksforGeeks

[2] [3] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [20] [21] [22] [24] Detecting C and C++ Memory Bugs with AddressSanitizer (ASan) | by Can Özkan | Medium

[4] [11] [23] Understanding AddressSanitizer: Better memory safety for your code – The Trail of Bits Blog

[12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [25] [26] [27] HOWTO: Use Address Sanitizer | Ohio Supercomputer Center

https://www.osc.edu/resources/getting_started/howto/howto_use_address_sanitizer